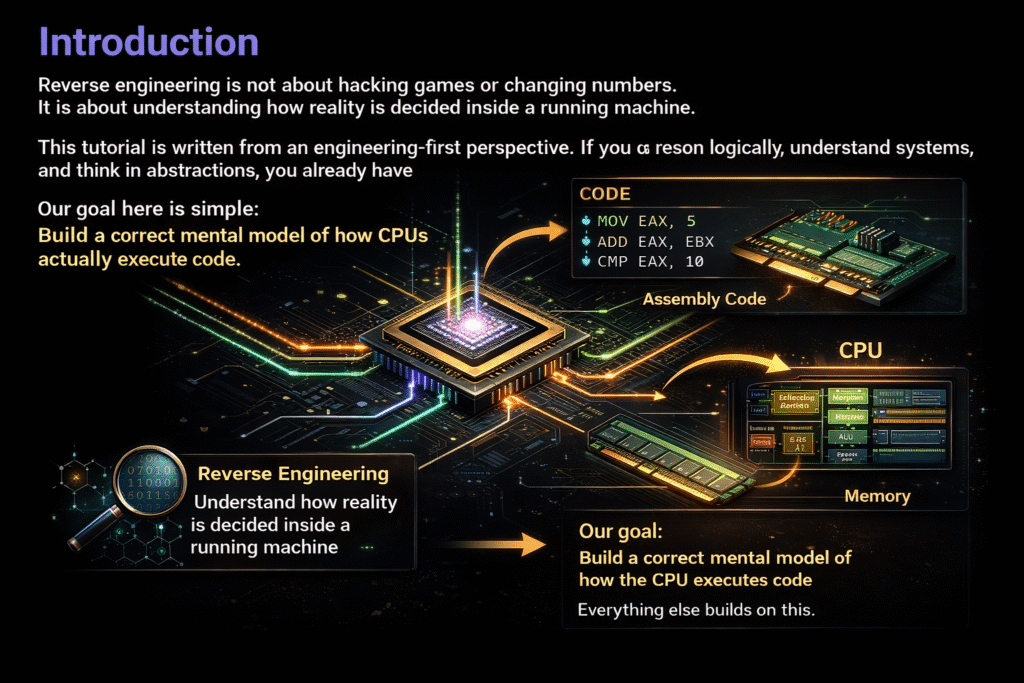

Introduction

Reverse engineering is not about hacking games or changing numbers.

It is about understanding how reality is decided inside a running machine.

This tutorial is written from an engineering-first perspective. If you can reason logically, understand systems, and think in abstractions, you already have what most people lack.

Our goal here is simple:

Build a correct mental model of how CPUs actually execute code.

Everything else builds on this.

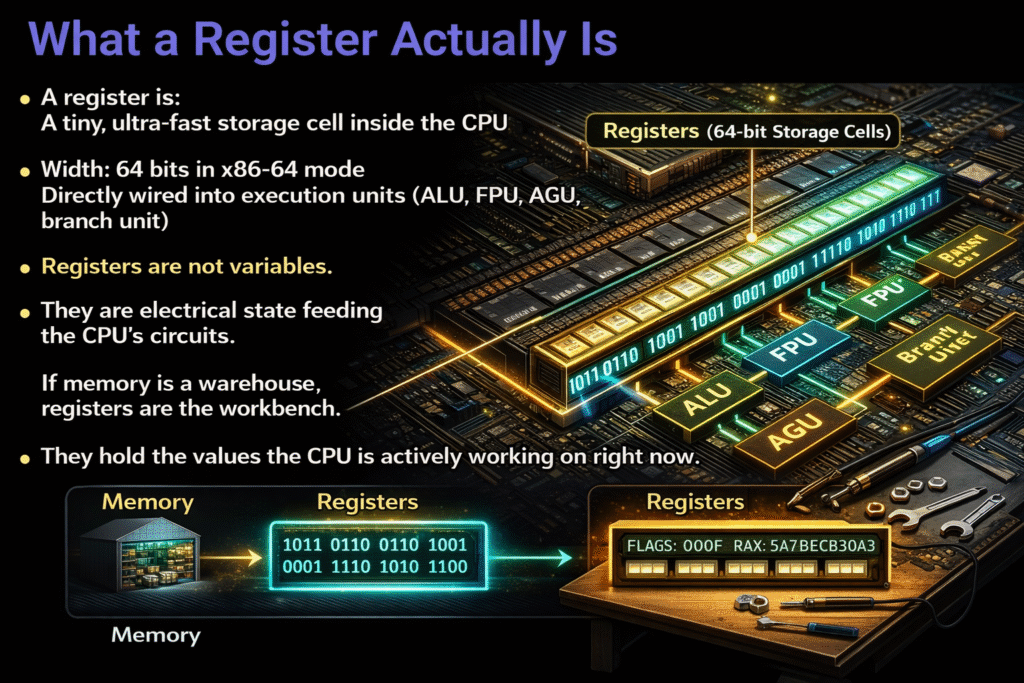

What a Register Actually Is

A register is:

A tiny, ultra-fast storage cell inside the CPU

Width: 64 bits in x86-64 mode

Directly wired into execution units (ALU, FPU, AGU, branch unit)

Registers are not variables.

They are electrical state feeding the CPU’s circuits.

If memory is a warehouse, registers are the workbench.

They hold the values the CPU is actively working on right now.

The Architectural Register Set (x86-64)

In 64-bit mode, the general-purpose registers are:

RAX, RBX, RCX, RDX

RSI, RDI

RBP, RSP

R8–R15

RIP (special)

Each register has historical bias, not strict rules.

The CPU does not care about “purpose”. The ABI (Application Binary Interface) does.

The ABI is a contract between functions. Breaking the contract causes crashes.

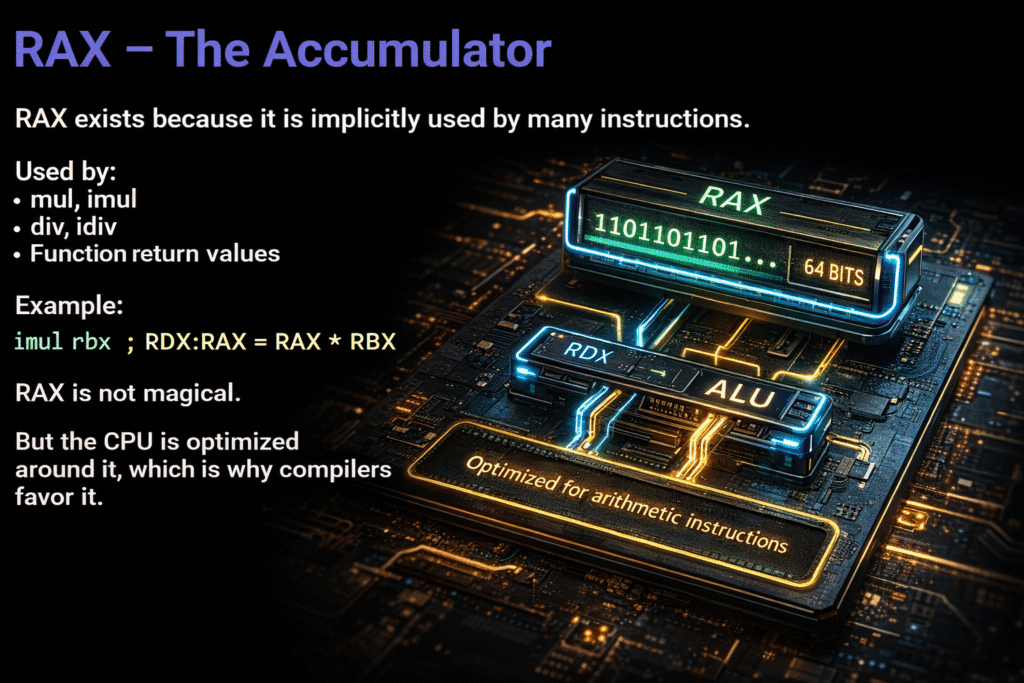

RAX – The Accumulator

RAX exists because it is implicitly used by many instructions.

Used by:

mul, imul

div, idiv

Function return values

Example:

imul rbx ; RDX:RAX = RAX * RBX

RAX is not magical.

But the CPU is optimized around it, which is why compilers favor it.

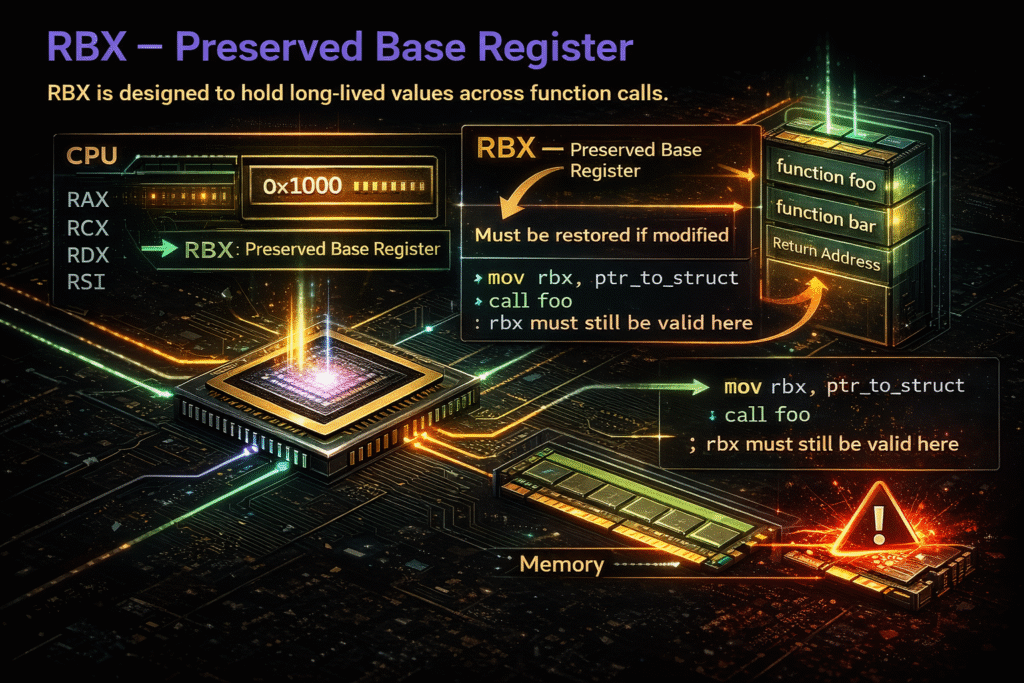

RBX – Preserved Base Register

RBX is designed to hold long-lived values across function calls.

The ABI rule:

If a function modifies RBX, it must restore it before returning.

Example:

mov rbx, ptr_to_struct

call foo

; rbx must still be valid here

If foo destroys RBX, the caller is corrupted.

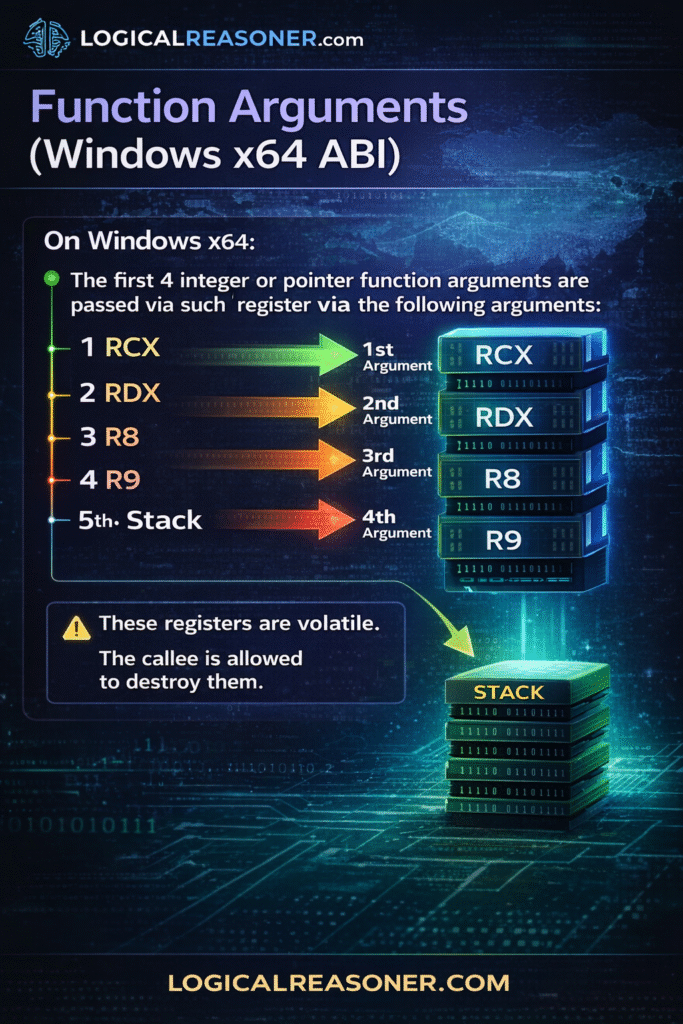

Function Arguments (Windows x64 ABI)

On Windows x64:

Argument Register

1 RCX

2 RDX

3 R8

4 R9

5+ Stack

These registers are volatile.

The callee is allowed to destroy them.

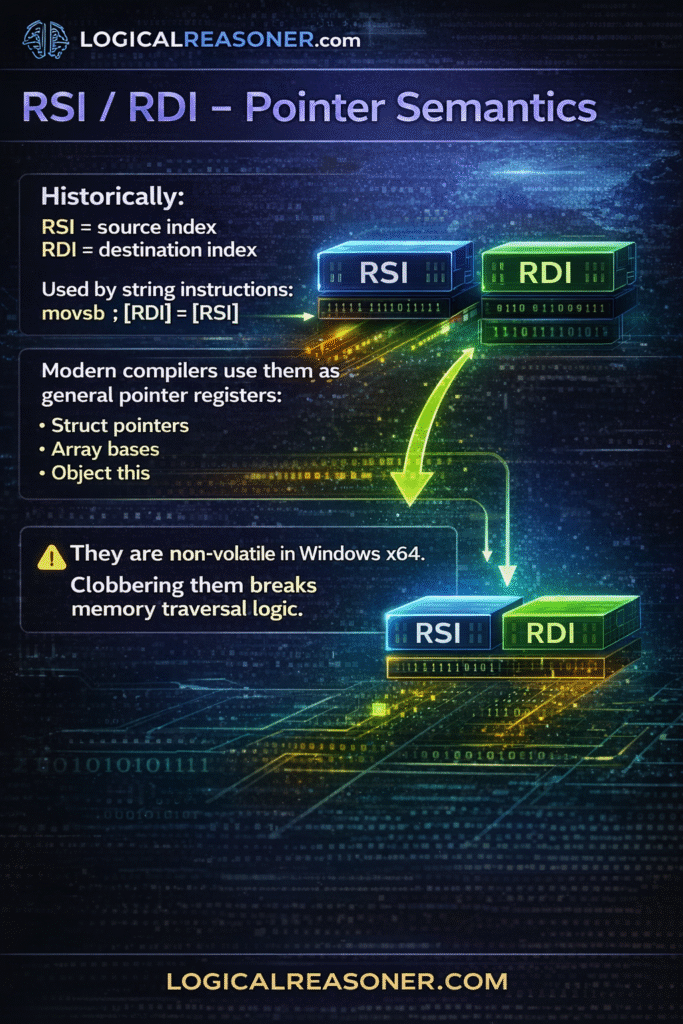

RSI / RDI – Pointer Semantics

Historically:

RSI = source index

RDI = destination index

Used by string instructions:

movsb ; [RDI] = [RSI]

Modern compilers use them as general pointer registers:

Struct pointers

Array bases

Object this

They are non-volatile in Windows x64.

Clobbering them breaks memory traversal logic.

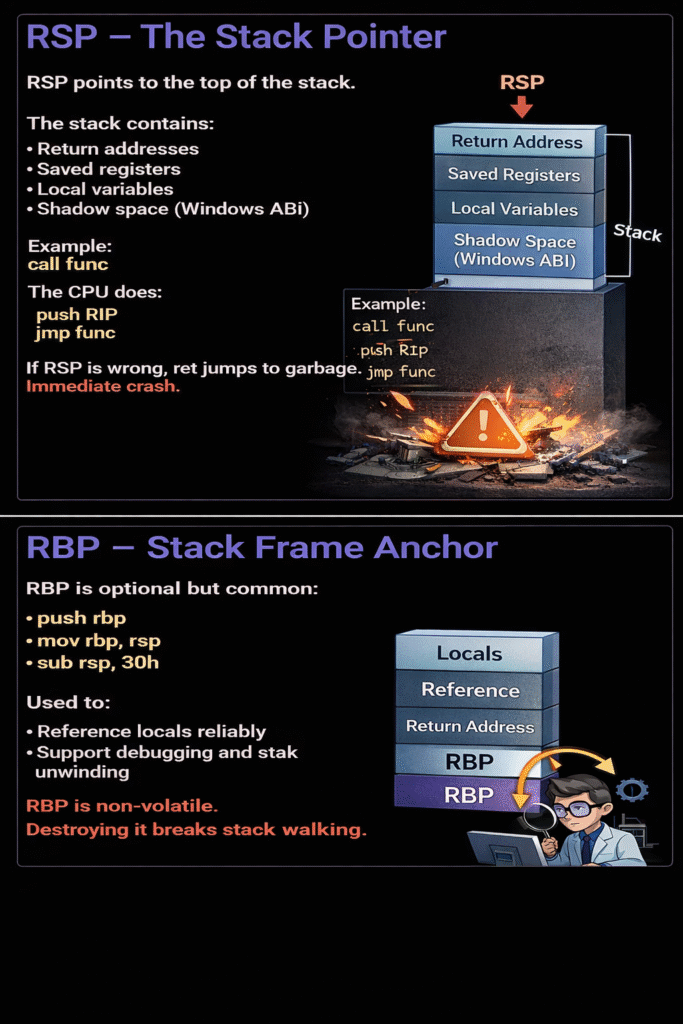

RSP – The Stack Pointer

RSP points to the top of the stack.

The stack contains:

Return addresses

Saved registers

Local variables

Shadow space (Windows ABI)

Example:

call func

The CPU does:

push RIP

jmp func

If RSP is wrong, ret jumps to garbage.

Immediate crash.

RBP – Stack Frame Anchor

RBP is optional but common:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 30h

Used to:

Reference locals reliably

Support debugging and stack unwinding

RBP is non-volatile. Destroying it breaks stack walking.

RIP – Instruction Pointer

RIP points to the next instruction.

You cannot write to it directly.

It changes only via:

jmp

call

ret

Conditional branches

Exceptions

This is why hooks work:

jmp newmem

You hijack control flow.

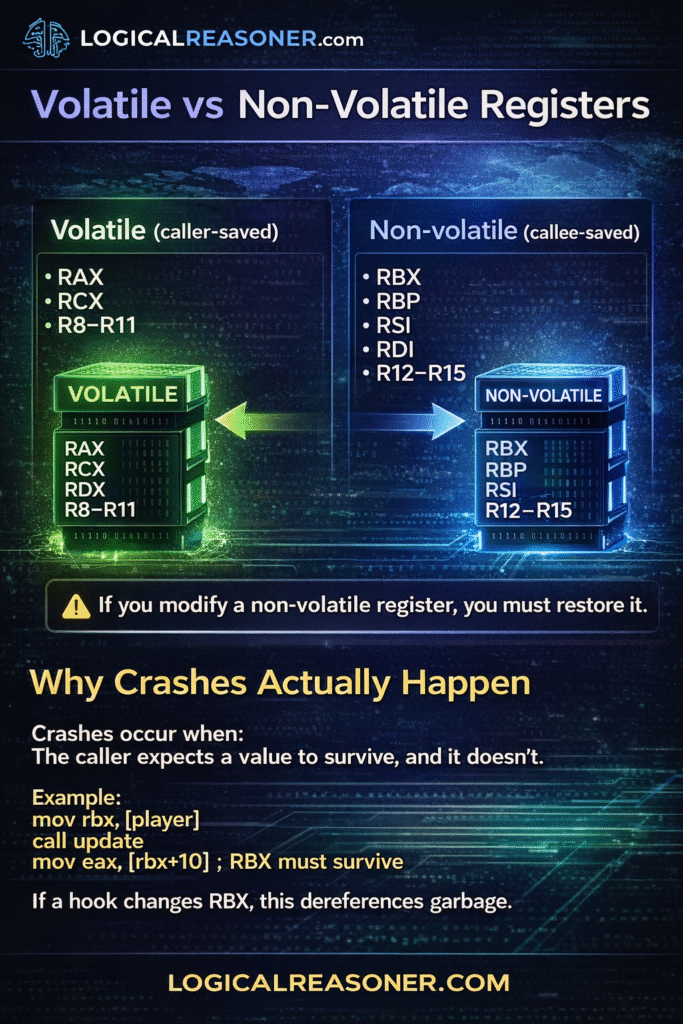

Volatile vs Non-Volatile Registers

Volatile (caller-saved)

RAX

RCX

RDX

R8–R11

Non-volatile (callee-saved)

RBX

RBP

RSI

RDI

R12–R15

If you modify a non-volatile register, you must restore it.

Why Crashes Actually Happen

Crashes occur when:

The caller expects a value to survive, and it doesn’t.

Example:

mov rbx, [player]

call update

mov eax, [rbx+10] ; RBX must survive

If a hook changes RBX, this dereferences garbage.

The Real Mental Model

Think like this:

Registers are shared state

ABI is a contract

Crashes are contract violations

Reverse engineering means:

Identifying which parts of the contract are active at a given instruction

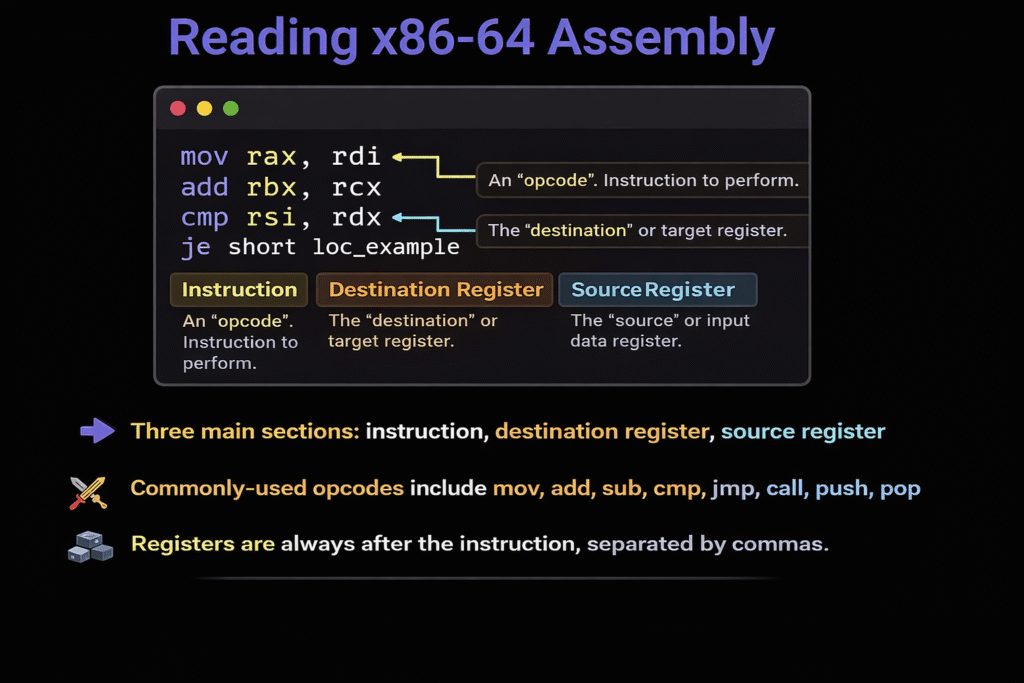

What an Opcode Is

An opcode is the byte-level command the CPU decodes to perform an operation.

Example:

mov eax, ebx

The CPU actually sees:

89 D8

89 → opcode (move r/m32, r32)

D8 → ModR/M byte (register encoding)

Assembly mnemonics are human labels. Opcodes are truth.

Instruction Encoding

An x86-64 instruction can be:

[Prefix][REX][Opcode][ModRM][SIB][Displacement][Immediate]

Example:

mov rax, rbx

Encoded as:

48 89 D8

Hooks overwrite bytes, not instructions. AOB scans depend on byte stability.

Opcode Families (How to Learn Efficiently)

You do not memorize thousands of opcodes.

You learn families.

Data Movement

mov, movsx, movzx, xchg, lea, push, pop

Arithmetic

add, sub, imul, mul, inc, dec, neg

Logic

and, or, xor, shl, shr, sar

Control Flow

jmp, je, jne, call, ret

Floating Point (SSE)

movss, addss, mulss, divss

Recognition matters more than memorization.

Final Principle

You stop thinking:

“This is a mov instruction.”

You start thinking:

“This byte pattern transfers ownership of state.”

That shift is the beginning of real reverse engineering.